As if to illustrate the truth of the biblical adage that a prophet is not without honor, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house, Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón, an internationally prominent champion of human rights, was recently suspended from his nation’s high court for abuse of judicial authority.

With varying degrees of success and to nearly universal praise, Garzón had taken or assisted in legal actions against Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, Bosnian Serb military leader and accused genocidaire Ratko Mladić, and the Salvadoran military officers who ordered the 1989 massacre of a Jesuit community.

But these were actions in international courts. When Garzón’s attention turned to his native Spain, and particularly to investigation of the responsibility born by Gen. Francisco Franco and 34 of his staff in the disappearance and mass murder of some 114,000 people during and after the Spanish Civil War, he soon found himself in legal trouble of his own. Garzon’s case is now before the Spanish Supreme Court, and a guilty verdict could expel him from his seat.

Whether legally or not, Garzón had violated the “pacto del silencio,” the “pact of silence,” which has governed Spanish memory during the time of the Franco dictatorship, from 1939 to 1975 and well into the years of Spain’s transition to democracy. Dartmouth professor Antonio Gomez Lopez-Quinones suggests the severity with which many Spaniards regard such violations by observing that “for a couple of decades, any challenge to this rule of silence was postulated as an inconvenient or irresponsible attack on a peaceful, delicate and finally successful process of negotiation between conflicting ideological forces.”

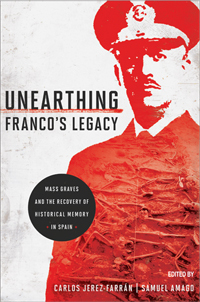

The observation is part of his essay, “Toward a Pragmatic Version of Memory,” which appears in a remarkable book titled “Unearthing Franco’s Legacy,” recently published by the University of Notre Dame Press.

Edited by Carlos Jerez-Farrán, professor of Spanish and fellow of Notre Dame’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies, and his former Notre Dame colleague Samuel Amago, now associate professor of Spanish at the University of North Carolina, “Unearthing Franco’s Legacy” is an anthology of historical, literary and journalistic essays concerning the discovery and exhumation of the mass graves of the Franco regime’s mostly anonymous victims nearly three-quarters of a century after it came to power.

The book is the product of an interdisciplinary symposium organized by Jerez-Farrán and held at Notre Dame five years ago. If its variegated participants had anything in common, it was a principled opposition to “the pact of silence,” the repression of collective memory beneath which the ancient wounds of a nation, people and culture continue to fester.

Only a week ago, controversy erupted in Spain when the country’s Royal History Academy published a publicly funded biographical encyclopedia which euphemistically described Franco’s government as an “authoritarian” one rather than a dictatorship, and praised the Generalissimo’s ruthlessness as “courage.”

This refusal to participate in what Milan Kundera called “organized forgetting” has implications far beyond the borders of Spain, and “Unearthing Franco’s Legacy” is not only a poignant attempt to achieve a consensus of memory, but also an example of how memory itself can become a moral task.

“The psychohistorical dynamics of ignored atrocities and systematic assaults on truth and memory are of universal concern,” Jerez-Farrán and Amago write in introduction of these essays. “In all cases, denial is anathema because national amnesia—enforced or unconscious—about given genocides has the potential to provoke new ones.”

In one of Spain’s mass graves lie the as-yet unidentified remains of the poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, who observed three years before the outbreak of his country’s civil war that “a dead man in Spain is more alive when dead than anywhere else in the world: his profile hurts like a razor’s edge.”

As a scholar of Spanish literature, Jerez-Farrán has specialized in Lorca’s work, and, with “Unearthing Franco’s Legacy,” put that razor’s edge to noble use.