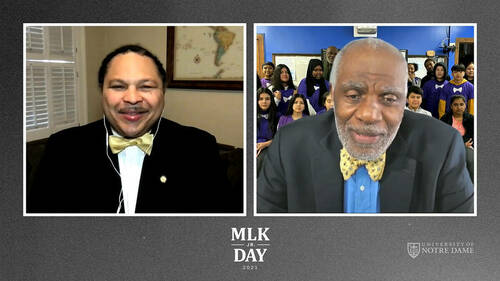

University of Notre Dame alumnus and retired former Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Alan Page challenged the idea of originalism with respect to the U.S. Constitution and proposed revisiting the founding document every 50 years during an hour-long conversation with G. Marcus Cole, the Joseph A. Matson Dean and Professor of Law at Notre Dame Law School, in commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

“Our Constitution is grounded in racial bias,” said Page, a 1967 Notre Dame graduate and member of the college and pro football halls of fame. “If we’re going to go back to the words of Jefferson and Lincoln and Madison and decide how we live today, those words were grounded in slavery. How do we untether ourselves from that?”

He proposed, “What if we had an amendment that said every 50 years we look at the words in the Constitution and give them their current meaning? That would break us from the past and actually give us a Constitution that works in the present.”

Touching on issues of race and the law, as well as Page’s childhood and his decision to come to Notre Dame, the online conversation took place amid a nationwide reckoning around issues of racial justice, including the treatment of Black people by police, and less than two weeks after a violent mob with ties to white nationalist organizations stormed the U.S. Capitol in protest of the election, leaving five people dead.

Amid such turmoil, Cole asked, “What should we be doing, not just as a society but as individuals, to come closer to Dr. King’s dream of an America where we’re judged on the content of our character?”

“As a judge you’re there to exercise your judgment, not impose your will, and because of that you have to constantly question yourself about your motivation for the decisions you’re making,” said Page, a native of Canton, Ohio, who earned All-American and Academic All-American honors as a member of the 1966 national champion Notre Dame football team. “You have to be intentional about it. You can’t say ‘I’m not biased’ and move on. We’re all biased.

“So as people, as individuals, we have to look internally,” Page said, “and ask ourselves, ‘Are the decisions I’m making based on some stereotypical view of people other than me? Or is it based on some objective criteria, on who the person is?”

At the same time, “We need to stop segregating ourselves,” he said. “We segregate ourselves in our homes, in our workplaces, in our communities. We’ve got to stop doing that.”

Monday marked the first MLK Day since the death of George Floyd.

Floyd, a Black man, was killed by a white Minneapolis police officer in May of last year, igniting a summer of sometimes violent and destructive protests and sporadic clashes between far-right and anti-fascist groups, and inspiring the ongoing movement for racial justice, including Black Lives Matter.

His death was captured on video.

“It seems to me that people have reacted differently to the killing of George Floyd than they have to all of the hundreds of other innocent people who have been killed by the police before him,” Cole said, asking, “What do you think is the reason for the reaction this time around?”

“I think the jury is still out on that. I’m not convinced that five years from now anything will be different because of it,” said Page, who spent most of his 15-year NFL career in Minneapolis, as a member of the Minnesota Vikings, and ultimately settled there when his playing career ended. “I hope that it will, that what we’ve seen so far will be sustainable. But I think the reason we’re seeing what we’re seeing so far is because all of a sudden, in stark relief, we see somebody dying at the hands of a police officer in a way that, from all outward appearances, leads someone to believe that it shouldn’t have happened.”

Also, he said, “It’s the realization that it’s done in our names. What took place was done in my name.”

Asked about backlash to the Black Lives Matter movement, and in particular the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and the charge that it is racist, Page said, “That kind of thing drives me crazy. We’d rather have a discussion about the name than the underlying root cause. That’s one of the reasons I say it’s not clear to me that things are going to change. Until we get at the root cause of these deaths we’ll just keep having this same discussion.”

As for the forceful response from law enforcement to last summer’s BLM protests, compared with the weak response to recent far-right protests, Page was quick to condemn violence and vandalism on both sides, saying, “Those are one and the same and both deserve the same treatment.”

He cautioned, however, about false equivalence, particularly with respect to the violent occupation of the Capitol.

“As Americans we have a tendency to look for easy answers; there was violence over here, there was violence over there. But when you look at what took place at the Capitol, there was a lot more going on than just people marching in protest. And I might add, marching in protest of a lie,” Page said, referring to unproven claims, from the president and key Republican allies, of widespread fraud in the election.

Page earned his law degree from the University of Minnesota while still playing for the Vikings, and even practiced law in the offseason. He was appointed assistant to the Minnesota attorney general in 1985 and assistant attorney general in 1987. In 1992, he was elected to the Minnesota Supreme Court as the first African American to serve on the court. He served three-plus terms before his mandatory retirement at the age of 70.

Reflecting on his early interest in the law, Page described it as a consequence of the social unrest of the 1950s and ’60s, as well as a desire to forge a life outside of working-class Canton.

“If things went well, I might be able to get a job in the steel mills,” he said of the prospects for a young, non-college-educated Black man in Canton at the time. “And from my vantage point, steel mills were dirty and dangerous and the work was repetitious.”

On the other hand, he said, “The few stories I knew about lawyers all involved lawyers making lots of money, not working too hard and driving fancy cars … and I probably watched a little too much ‘Perry Mason’ too.”

Of equal importance, he said, “In 1954, when I was 8 years old, the United States Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education,” outlawing segregation in public schools. “And even at a young age, not understanding what the law was about or anything else, I intuitively understood that decision in Brown had tremendous impact. And from that I got the sense of the power of the law.”

As for the decision to attend Notre Dame, Page chalked it up to academics.

“Growing up having heard the legend of Knute Rockne, that had some impact. And knowing the stories of the history of the football program, that had some impact,” he said. “But it also seemed to be that of the three schools I was considering, Notre Dame had the … academic prestige that the other two didn’t have.”

Page ultimately graduated with a degree in political science. These days, he supports young people of color in Minnesota through the Page Education Foundation, a scholarship program that has awarded more than $15 million to more than 7,500 students.

Monday’s talk was sponsored by the Office of the President, Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., and the President’s Oversight Committee on Diversity and Inclusion as part of Walk the Walk Week. It included opening remarks by Father Jenkins, along with an invocation from senior Kaya Lawrence. Lawrence is a political science and global affairs major from New Orleans with a concentration in peace studies. She is director of diversity and inclusion for Notre Dame Student Government.

A weeklong series of events designed to promote diversity and inclusion within the Notre Dame community, Walk the Walk Week will take place Feb. 22-28 this year because of changes to the academic calendar related to the coronavirus pandemic.

For more information, visit diversity.nd.edu/walk-the-walk.