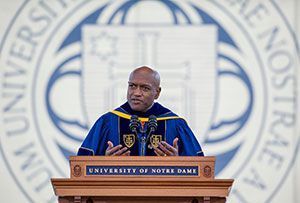

Delivered at Notre Dame’s 169th University Commencement Ceremony, held May 18, 2014, in Notre Dame Stadium

Rev. Ray Hammond, 2014 Commencement speaker

Rev. Ray Hammond, 2014 Commencement speaker

My sincere thanks to Father Jenkins, to the trustees, the faculty and staff and to the many members of the South Bend community who have so graciously welcomed and hosted us; my congratulations to my stellar fellow-honorands; and, most especially, my thanks to the class of 2014 for the privilege of participating in this very special celebration. I am, as you know, the backup speaker for today, and I hope you’ll join me in offering up prayers for Lord Christopher Patten — a man who has served his country, our world and God’s Kingdom boldly and justly. I also want to give a special shout-out to my fellow-honorand and friend, His Eminence Seán Cardinal O’Malley. You can take it from an African Methodist Episcopal pastor who serves with him in Boston that he has been an incredibly healing presence in a traumatized community and the Archdiocese he leads has been an invaluable partner in turning back the tide of violence. For his partnership and friendship, I am deeply grateful. And then, graduates like you, I have in this audience a posse of friends and family members for whose presence I am deeply thankful. I must particularly acknowledge my wife, whom I met in college and, in spite of the fact that, as she puts it, “I was not her type,” she married me anyway. She’s been my friend, she’s been my fellow-laborer in raising a family, building a church and making a contribution to the global community. After almost 41 years of marriage, I can never be thankful enough to her and to God for allowing me to be her husband.

Now, that’s it for the introductory remarks because I only have about 15 minutes to address you. This is a bit of challenge for me as a preacher coming out of the African-American tradition and we usually take 15 minutes to say hello. But mindful of the occasion and my constraints, I say to you what Kim Kardashian told Kris Humphries and that is, “I am not going to keep you long.”

Just long enough, graduates, to remind you that this is a day for looking back nostalgically over the years you have just spent at this iconic institution, Notre Dame. And just as you may be experiencing a flood of emotions, so too are your family and friends. I don’t know if you can fully appreciate the joy we feel as we watch young women and men — as bright, gifted, imaginative and beautiful as you are — coming to this milestone in your lives. You are the children, and now the young leaders, that we dreamed about, prayed for and longed to see. You have made us laugh and you have made us cry, frequently at the same time. We have gotten on your last nerve and you have certainly gotten on ours. But on this day, we celebrate together the immense joy you have brought to our lives and the high hopes that we have for you and for your future. This is your day because it could not have come to pass without your personal commitment to hard work and sacrifice. And this is our day because it could not have come to pass without personal commitment to hard work and sacrifice. Graduates, my simple request, as you move to the next stages in life is that you remember that gift, that grace and that you pass that it on. Turn to your neighbor to the right and ask them to pass it on.

Now I ask this of you because I am keenly aware of the connection between individual effort and collective support. You’ve heard or read a little of my story, but what you do not know is that I grew up in Philadelphia at a time when gang warfare was rife, drugs were on the increase and many young women and men were wasted by the streets. I’m here today, not simply because I’m smart or a hard worker, but because of the grace of God and because of the loving care of so many people, especially my parents. My mother, the first person in her family to ever go to college, dropped out of college during World War II because it was too expensive and her family needed her help; but she never forgot her dream of becoming an educator. So when her young children entered school, she went back to school to finish her BA, get her M.Ed. and become a master teacher in the Philadelphia public schools. My father got his bachelor’s at the age of 50, and when he died at the age of 72 he had recently started working on his master’s degree in theology. And despite all of the demands of their own quest for growth and excellence, they always had time to help their children go even farther than they had gone. Sure I worked hard, but I am not confused. I was tremendously blessed by the gift of grace, an unmerited favor, from others.

I had elementary school teachers, like Mr. Finkelstein and Mrs. Shepard, who had high expectations for me and who even higher support to me. There were the church members and friends who always gave encouragement with words about how much progress I had made. There were civil rights marchers and protestors who fought and, in some cases died, to open doors of opportunity that had remained shut to people like me for 400 years of this nation’s history. I, like you, am the recipient of a wonderful gift of grace from God and from others and I have to pass it on.

That’s why I am convinced that there is no more dangerous or delusional myth than that of the self-made man or woman. No one is now or has ever been self-made. Whenever we stand tall, and you are standing tall today, it’s because we stand on the shoulders of giants. We are the recipients of a wonderful grace and I pray that you will pass it on.

Let me tell you an example of how just how powerful passing it on can be. I offer the apocryphal but poignant story first shared with me by a mentor and friend, Marian Wright Edelman. On the first day of school, Jean Thompson stands in front of her fifth-grade class and tells her children a lie. She tells them that she loves them all the same and that she would treat them all alike. But in the beginning that was impossible because there in front of her, slumped in his seat on the third row, was a boy named Teddy Stoddard.

Mrs. Thompson already knows that Teddy doesn’t play well with the other children, that Teddy’s clothes are unkempt, that Teddy needs a bath, and that Teddy is generally unpleasant.

But slowly what Jean Thompson felt and thought she knew about Teddy began to unravel. Because one day she reads Teddy’s file and, boy, was she surprised. Teddy’s first-grade teacher wrote, “Teddy is a bright, inquisitive child with a ready laugh. He does his work neatly and has good manners … he is a joy to be around.” His second-grade teacher wrote, “Teddy is an excellent student, well-liked by his classmates; but he is troubled because his mother has a terminal illness and life at home must be a struggle.” His third-grade teacher wrote, “Teddy continues to work hard but his mother’s death has been hard on him. He tries to do his best but his father doesn’t show enough interest and his home life will soon affect him if some steps aren’t taken.” And then, Teddy’s fourth-grade teacher wrote, "Teddy is withdrawn and doesn’t show much interest in school. He doesn’t have many friends and he sometimes sleeps in class. He is tardy and he really could become a problem.”

Jean Thompson was beginning to understand the problem, but, before she could think about what to do, the Christmas season was upon her. There was the school play and the other festivities, so it was not until the last day before the holiday vacation began that she was abruptly brought back to the subject of Teddy Stoddard. It happened as each of her children brought her Christmas gifts, wrapped in gay ribbon and bright paper, except for Teddy, whose gift was clumsily wrapped in the heavy, brown paper of a cut-up grocery bag. When she opened that bag, some of the children started laughing because in it was a rhinestone bracelet with several missing stones and a bottle that was only one-quarter full of perfume. She ended their laughter when she put the bracelet on and said, “Oh, this is really pretty,” and then dabbed some of the perfume onto her other wrist while declaring that it smelled so sweet. Teddy stayed behind just long enough to tell Jean Thompson that the bracelet and the perfume had belonged to his mother, and as he left he said this: “Mrs. Thompson, today you smelled just like my mom used to.” After Teddy left, she cried and asked God to forgive her for her self-absorption, her blindness and her failure to remember that, but for grace, Teddy’s story would be her story. She also promised God that she would stop teaching reading, and writing, and arithmetic. Instead, she would teach children.

She kept her promise and she paid particular attention to a child named Teddy. The more she worked with Teddy, the more his mind seemed to come alive. The more she encouraged him, the faster he responded. On days there would be an important test, she would wear the rhinestone bracelet and the perfume. By the end of the year Teddy had become one of the smartest kids in the class and he had become special to a teacher determined to make a difference where that difference mattered most.

Teddy left her class, but a year later she found a note under her door, telling her that of all the teachers he’d had in elementary school, she was his favorite. Six years later she got another note from Teddy. He wrote that he had finished high school, third in his class. Four years later, another note, saying that while things had been tough, he’d stayed in school and would graduate from college with honors. Then four more years passed and yet another letter came. Teddy wrote that he had decided to go a little further, and the letter was signed, Theodore F. Stoddard, M.D.

The following spring there was a final letter. Teddy said he was getting married. His father had died a couple of years ago and he had no real blood family. But he was wondering if Mrs. Thompson might agree to sit in the pew usually reserved for the mother of the groom. And she sat in that pew and witnessed the difference that it makes when the gift of grace in your own life is passed on to someone else.

So, graduates, you’re the recipients of a great grace and my simple request is that you pass it on. Tell your neighbor on the left, pass it on. And how about this: I challenge you to have the courage to pass it on to people who are not the usual suspects — the people that others have written off — the least, the lost, the left out; the abused, the abandoned, the incarcerated, the poorly educated, the unborn, the near-dead, the immigrant, the homeless, the trafficked, the marginalized of every stripe and description — the folks, the families, the neighborhoods and the nations whose challenges and failures, like Teddy Stoddard’s, are well-known and widely trumpeted, but whose possibilities are rarely appreciated.

So pass it on, because you take to heart the words of Jesus who declared, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” Or because the words of Father Gustavo Gutierrez ring in your ears as he says, “(Neighbor is) not he whom I find in my path, but rather (s)he in whose path I place myself, he whom I approach and actively seek.” Or because you believe like Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American elected to the House of Representatives, who said, “Service is the rent that you pay for privilege of living on this earth.”

This is a lesson that God has imprinted on my life time and time again. Every time I meet with young women and men caught up in the violence of urban streets — the Teddy Stoddards with hats to the back and pants down real low, and guns not far away — I know that this is not charity; this is just me, a much older urban kid, passing on the grace of God to a younger urban kid. When my wife and I found ourselves standing on a hot savannah on the Fourth of July in South Sudan with a thousand women and children who had been rescued from servitude in northern Sudan, this was not charity; this was two proud descendants of another century’s slaves passing the grace of presence and solidarity on to this century’s slaves. And then there was Northern Ireland and the walking tour with a friend and former IRA man, who was now working for peace between Protestant and Catholic communities. As we walked through the shattered and largely deserted ruins of that Belfast street on which he grew up, he stopped and said, “Ray, I want to show you something that was a source of inspiration and hope for me through many of the darkest days.” We rounded a corner to behold a giant mural of Martin Luther King with the caption reading, “Injustice anywhere is an affront to justice everywhere.”

Graduates, pass it on. Tell the neighbor behind you to pass it on. Pass it on as more than 200 of your classmates are doing in a postgraduate year of service. Pass it on by thinking less about your career and more about your calling — your calling to become educators, who like Jean Thompson, teach people, not subjects; your calling to become lawyers who are deeply committed to justice; your calling to becoming physicians committed to healing people and not just diseases; your calling to be businesspeople with a sense of sacred stewardship over the resources and people entrusted, not to their management, but to their servant-leadership; your calling to be artists who preserve and extend our common culture and give us new insights and visions of beauty; your calling to be scientist and engineers and architects who explore, reveal, reshape and even heal God’s creation; your calling to become parents who not only have children but who raise children and love children; and citizens who don’t just ask what’s good for me, but what’s good for all of us, especially the people I don’t know and I don’t like.

Now, you’re a graduate, a Notre Dame graduate, I know that you will never forget the God quad, Touchdown Jesus, First-Down Moses, the joys of LaFun, praying at the Grotto for finals, and the fact that you can now walk up the front steps of the Golden Dome. But my fervent prayer is that you will always remember the gift of grace you have received — the grace of parents who love you, the grace of friends who embrace you, the grace of teachers who have taught you, and the grace of opportunities that lay before you. And for your sake and God’s sake I pray that you pass it on. God bless you.