Jason Quinn

Jason Quinn

On Sunday (Oct. 2), Colombians narrowly rejected a peace deal that the country’s president and largest rebel group had signed just days before.

The “no” vote — while surprising in light of recent polling trends — was somewhat predictable given what we know of other peace agreement referendums and social media analysis, according to Jason Quinn, research assistant professor in the Peace Accords Matrix (PAM) project at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

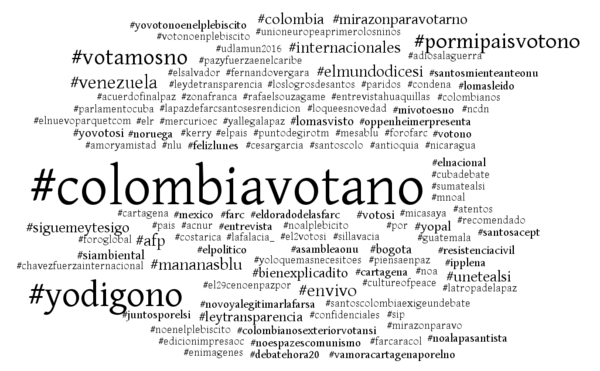

“PAM researchers analyzed thousands of tweets and the corresponding hashtags concerning the referendum in Colombia over the last several months,” said Quinn. “Tweets with a hashtag containing the word ‘no’ were much more prevalent. Our analysis shows that the ‘no’ campaign had a much more organized and extensive social media campaign than the ‘yes’ pro-accord camp.” The Twitter analysis on the Colombian referendum was done by Henry Dambanemuya, a master’s student in international peace studies, who is spending this semester working on the PAM project with Madhav Joshi, Associate Director of PAM.

And it’s not the first time a peace deal has been voted down in a public referendum, according to Quinn.

“In Guatemala in 1999, the 50 core constitutional amendments in the peace agreement were voted down in a public referendum by less than a 1 percent margin with a nationwide turnout of 18 percent,” he said.

“Counting on the turnout of educated, urban dwellers in the capital, the ‘no’ campaign in Guatemala was waged via numerous front-page full ads in the leading newspapers urging readers to vote no to dangerous and subversive reforms. The same happened in Colombia.”

Quinn said several factors explain the “vote no” advantage in Colombia, Guatemala and other cases.

“The simplest one is that governments, in the months before an agreement is signed, are typically working frantically and expending all energy toward negotiating and signing the final agreement, while the ‘no’ campaign is free to spend 100 percent of its time opposing the deal,” Quinn said.

“Second, social psychology experiments show that people have a tendency to oppose propositions they don’t understand well and peace accords are complex legalistic instruments.

“Third, civil wars tend to be fought in the countryside, not the cities. This means those mostly likely to vote are also those least affected by the costs of civil war. All these forces translate into more ‘no’ votes in civil war peace processes.”

Quinn said President Juan Manuel Santos could frame the referendum result as a “no” vote on the peace agreement in its current form and make it clear that the public still supports the peace process but desires re-negotiation of some sensitive cultural issues and language.

Another step is to get “vote no” leaders to join the negotiations to review the contested terms in the accord, then have another referendum or ratify the revised accord in congress.

PAM is the formal technical implementation support body in the Colombian Peace Agreement for which Quinn is a principal researcher. He has provided mediation research support, written policy briefs and provided recommendations in negotiation processes in Myanmar, Nepal and Colombia.

PAM is the world’s leading academic center for measuring the progress of peace agreements on a systematic comparative basis. Its database tracks the implementation status of 34 recent comprehensive peace accords by assessing 51 distinct provisions year-by-year for 10 years in quantitative and qualitative form.

The Kroc Institute is an integral part of Notre Dame’s new Keough School of Global Affairs. The Keough School seeks to addresses some of the world’s greatest challenges, with particular emphasis on the design and implementation of effective and ethical responses to poverty, war, disease, political oppression, environmental degradation and other threats to dignity and human flourishing.

Contact: Jason Quinn, 574-631-0997, jquinn12@nd.edu