Early in his life, he was called aphenomenon among sculptorsby none other than the great French artist Auguste Rodin.

In 1947, he became the first living artist to have a one-man show atNew Yorks Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A national hero in his nativeCroatia, he was considered throughout his career as the worlds greatest living sculptor of religious works of art.

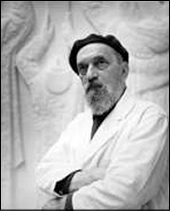

He was Ivan Metrovi, who 50 years ago joined the Notre Dame faculty as a distinguished professor and artist-in-residence. Though he worked and taught at the University for just seven years, until his death in 1962, he ranks among the most distinguished faculty members in its history, and his legacy lives on in the form of multiple works throughout the campus.

He would stand very near to the top, if not at the top,said Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., Notre Dames president emeritus, when asked where Metroviwould rank among the faculty appointments he made during his 35-year presidency.He was a person who was internationally recognized; he was known everywhere.

Metroviwas, indeed, an artist of worldwide fame, but he began his life in a humble setting – born the son of peasantsAug. 15, 1883, in the smallvillageofVrpolje,Croatia. His family moved to Otavice in the Dalmatian mountains of Croatia, and it was there that Metrovitended flocks, learned some artistic skills from his father, Mate, a stonemason, and received religious instruction from his mother, Marta Kurabas.

The wood carvings the young Metrovicreated began to draw attention in his little village and, with financial assistance from neighbors, he was sent toSplit, on the Croatian coast, to learn stone cutting in the workshop of a master mason named Pavao Bilinic. He learned quickly and, at age 16, he moved on toVienna, where he enrolled in theAcademyofFine Artsand met Rodin, architect Otto Wagner, painter Gustav Klimt, and other leading artists.

Though he was more conservative, Metrovibegan to exhibit his work with the Vienna Secession, a group of artists, including Klimt, that pushed the limits of art. During the first decade of the 20 th century, Metrovi, working mainly in wood and stone, exhibited inViennaand beyond. In the years immediately before, during and after World War I, he worked mainly inParisand, in the words of biographer Robert B. McCormick, became acelebrated sculptor of the first rank.

In the 1920s, Metrovifirst toured in theUnited States, exhibiting some 100 of his sculptures at the Brooklyn Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Detroit Institute of the Arts, and elsewhere. He enjoyed considerable success and was commissioned to createIndians,the bronze sculptures of Native Americans on horseback that stand on the west side of Grant Park inChicago.

Metrovireturned to live inCroatiain the late 1920s and during the next decade received numerous commissions to sculpt leading figures of the day. Gradually, however, he turned away from political subjects and concentrated increasingly on biblical themes.

When Axis troops invadedYugoslaviain 1941, Metrovirefused to cooperate and was imprisoned inZagrebfor almost five months. It was then that he began sketches that ultimately led toPieta,one of his most celebrated creations. The 7-ton marble sculpture of Nicodemus, Mary Magdalene and the Blessed Mother taking Jesus from the cross now stands permanently in Notre Dames Basilica of the Sacred Heart. The sketches, autographed by Metrovi, are in Father Hesburghs chapel on the 13 th floor of the Hesburgh Library.

With pressure from theVatican, Metroviwas released from prison and spent the remainder of War World II in exile inItalyandSwitzerland. At the conclusion of the war, with Marshal Tito ruling his homeland, Metroviaccepted an appointment to the faculty ofSyracuseUniversityin 1947. He remained there until 1955, when he met Father Hesburgh while the Notre Dame president was visiting family members in his hometown ofSyracuse.

I met Metrovithrough (the late Holy Cross priest and artist) Tony Lauck,Father Hesburgh recalled.When we met, he told me he was going to spend the rest of his life working on religious art. I asked if he would be interested in working at Notre Dame, and he said that his work probably would be appreciated here more than anywhere else.

At age 71, Metroviwas appointed to the Notre Dame faculty in January 1955. He received an honorary doctor of fine arts degree from the University in June, began teaching and working in September, and directed the relocation of hisPietafrom theMetropolitanMuseumto the Basilica in November.

Father Hesburgh remembers that in Metrovis first couple of years at Notre Dame, he would teach from8 a.m.untilnoon, go home for lunch and a nap, and then return in mid-afternoon to work on his art.

After a while, I said to him, Maestro, use the morning hours for your art, when you are fresh, and then teach in the afternoon,Father Hesburgh said.

Thats what he did, up to and including the day he died of a stroke at age 78 onJan. 16, 1962. He is buried inCroatiain a mausoleum he designed for his family.

In addition to hisPieta,several other Metrovisculptures adorn the Notre Dame campus, includingReturn of the Prodigal Sonin the Basilica,Swinson MadonnaandMadonna and Childin the Eck VisitorsCenter,MotherandAshbaugh Madonnain the Snite Museum of Art, andSaint Luke the Evangelist,Saint John the EvangelistandChrist and the Samaritan Woman at Jacobs Wellin the Shaheen-MetroviMemorial on the west side of OShaughnessy Hall.

Metroviwas a charter inductee on the Universitys Wall of Honor, a display in theMainBuildingthat recognizesexceptional men and women whose contributions to Notre Dame are lasting, pervasive and profound.

TopicID: 10182